What you'll learn:

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers Summary

👇 Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers video summary 👇

What’s the story of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers?

In the book “Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers” (1994), Robert Sapolsky, a respected professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University, explores the intricate science of stress.

The book delves into how stress affects our daily lives, acting as a helpful tool for immediate challenges but also posing potential health risks over time.

Sapolsky doesn’t just stop at explaining; he generously shares practical tips on how to effectively manage stress.

This insightful guide is not only rooted in science but also sprinkled with valuable advice for maintaining a balanced and stress-free life.

Who’s the author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers?

Meet Robert Sapolsky, the brain behind this enlightening exploration.

Beyond being a professor, he’s a renowned stress researcher, regularly contributing his expertise to magazines like Discover and The Sciences.

Sapolsky’s achievements extend to being a recipient of the MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant.

If that’s not impressive enough, he’s also the author of other notable works such as “A Primate’s Memoir” and “The Trouble With Testosterone.”

Who’s Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers summary for?

Anyone fascinated by the dynamics of health, happiness, nutrition, and science.

And for those wishing to learn how to maximize their power to their greatest benefit.

Why read Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers summary?

Stress is a buzzword in our modern lives, and this book promises more than just the usual advice. Instead of generic tips, you’ll unravel the true nature of stress – how it’s intricately woven into our daily existence.

Unlike zebras on the African savannah, humans have a unique relationship with stress, courtesy of our evolved and complex brains.

This opens the door to a variety of stressors, some even stemming from future concerns, unlike other mammals.

The impact of stress goes beyond mental discomfort. It takes a toll on our cardiovascular system, insulin production, reproduction, and, ultimately, our overall health.

This book isn’t just about highlighting the problem; it’s a guide that explains the intricate processes at play and, more importantly, provides actionable insights to help you tackle stress head-on.

In this summary, you’ll learn:

– The crucial role stress plays in making depression a leading cause of medical disability by 2020.

– Insights into why individuals with lower economic status are more prone to stress-related diseases.

– The surprising connection between stress and the development of diabetes.

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers Lessons

| What? | How? |

|---|---|

| 1️⃣ Humans stress over imaginary things | Practice mindfulness to distinguish real threats from imagined scenarios. Focus on the present moment and rationalize potential stressors. |

| 2️⃣ Our nervous system manages stress | Engage in activities that activate the parasympathetic nervous system, such as deep breathing or meditation, to promote relaxation. |

| 3️⃣ Our bodies prioritize short-term actions | Develop long-term strategies to manage stress, incorporating activities like regular exercise, adequate sleep, and healthy coping mechanisms. |

| 4️⃣ Stress can cause heart diseases | Prioritize cardiovascular health through a balanced diet, regular exercise, and stress-reduction techniques to mitigate the long-term impact of stress on the heart. |

| 5️⃣ Stress can increase the risk of diabetes | Adopt a healthy lifestyle, including proper nutrition and regular physical activity, to reduce the risk of diabetes exacerbated by chronic stress. |

| 6️⃣ Stress can increase depression | Foster emotional well-being by seeking social support, engaging in activities you enjoy, and addressing stressors to prevent the onset or exacerbation of depression. |

| 7️⃣ Stress affects our reproductive system | Prioritize stress management to support reproductive health. Establish a work-life balance, engage in relaxation techniques, and seek professional guidance if needed. |

| 8️⃣ Stress is unavoidable | Learn effective stress management techniques, including mindfulness, time management, and coping mechanisms tailored to your preferences. |

| 9️⃣ Take responsibility for your stress | Identify stressors you can control and take proactive steps to address them. Reframe your perception of stressors beyond your control to minimize their impact. |

| 🔟 Your income affects your stress levels | Focus on personal development, career advancement, and financial literacy to improve your income and reduce stress associated with economic challenges. |

| 1️⃣1️⃣ Income inequality promotes lack of trust | Advocate for social equality, support initiatives promoting fair economic practices, and engage in community-building activities to enhance social cohesion and reduce stress. |

1️⃣ Humans stress over imaginary things (unlike animals)

Ever wondered why stress seems to be an integral part of the human experience, especially when faced with situations that don’t involve immediate physical danger? Let’s unravel the mystery.

In the animal kingdom, stress responses are primarily triggered by tangible threats like physical danger and risk. Picture a zebra on the savannah, fleeing from a lion, or the lion itself, chasing a zebra for sustenance. Both scenarios demand urgent action for survival.

Some animals also contend with chronic physical stress, such as the need to cover extensive distances daily in search of food or water. However, for humans, stress often wears a psychological cloak – it’s the stress we create in our minds.

Think about those sleepless nights before a career-defining presentation, or the anxiety over a traffic jam, looming deadlines, finding a parking spot, or tense family discussions.

Unlike our animal counterparts, these situations seldom call for extraordinary physical responses; there’s no need for fistfights or daring escapes. Yet, they stir up stress in our minds.

What sets humans apart is our ability to stress over hypothetical situations in the future – worrying about mortgages, upcoming job interviews, or retirement funds.

While it makes sense to plan for these stressors, it becomes futile when we lack the ability to influence the situation causing our concern.

Here’s the fascinating twist: from an evolutionary perspective, sustained psychological stress is a relatively recent phenomenon.

It highlights how our complex brains, capable of conjuring up stress over imaginary scenarios, have introduced a new layer to the age-old response to danger and risk.

Understanding this origin story of stress sets the stage for exploring effective ways to manage and navigate the psychological challenges of our modern lives.

Onwards.

👉 Discover More:

- This Is How to Become a Millionaire in 6 Simple Steps

- So, Money Does Buy Happiness (Here’s How)

- Are You Doing These 8 Investing Mistakes Too?

2️⃣ Our nervous system manages stress (with 2 antagonistic systems)

Ever wondered why your body reacts so intensely when startled? Let’s uncover the science behind it and understand how our autonomic nervous system takes charge of our stress response and recovery.

Picture the last time someone gave you a good scare – the sudden alertness, focus, and that feeling in every fiber of your being.

This reaction is orchestrated by the autonomic nervous system, the unsung hero responsible for managing our body’s involuntary actions, like blushing, breathing, or even getting goosebumps.

This system is a tag team of two: the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. They work in opposition, playing a crucial role in our stress response.

The sympathetic system takes the stage during emergencies, real or perceived, regulating vigilance, arousal, activation, and mobilization. Some medical students even humorously refer to it as managing the four Fs: flight, fight, fright, and, well, you know the last one.

Originating in the brain, the sympathetic system extends its influence to every nook and cranny of your body – from organs and blood vessels to sweat glands and even the tiny muscles at the base of your hairs, giving you goosebumps when startled.

In contrast, the parasympathetic system steps in to promote calm and vegetative activities, fostering growth, energy storage, digestion, and similar processes. So, while the sympathetic system revs up your heart rate, the parasympathetic system puts the brakes on.

These systems are dynamic, capable of being activated at different speeds and for various durations. It’s like a finely tuned orchestra where nerves, acting like precise electrical cables, can stimulate or inhibit the activity of specific organs immediately.

This precision is crucial for survival – when facing a predator, your heart rate needs to skyrocket now, not in five minutes.

As a bonus, the brain releases hormones into the bloodstream, although slower than the nervous system, their effects linger throughout the body.

However, chronic elevation of these hormones can disrupt normal stress responses and recovery, emphasizing the delicate balance our bodies maintain in navigating the intricate dance between stress and recovery mechanisms.

Understanding this dance provides insights into how we can better manage stress for optimal well-being.

Next.

3️⃣ Our bodies prioritize short-term actions (when under stress)

Ever experienced getting sick right before an eagerly awaited vacation due to work stress? Turns out, your body’s response to stress plays a role in such unwelcome surprises.

Let’s dive into the biology lesson that explains how the human body prioritizes short-term, high-cost actions over long-term projects when under stress.

For mammals, stress is all about maximizing energy for muscles, a crucial component for survival. Unlike bacteria that can go dormant or plants that develop defenses, mammals, including humans, need to actively find food and escape danger – requiring the use of muscles.

To amp up energy levels, glucose and fat are swiftly moved through cells into the bloodstream. Simultaneously, heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing escalate, ensuring a rapid transportation of nutrients and oxygen.

However, here’s the catch – functions not immediately contributing to dealing with the imminent danger are put on hold to conserve energy. Digestion, tissue repair, sex drive, and the immune system take a backseat.

Imagine being a deer evading a hungry wolf – your energy is better spent on running than growing antlers, producing sperm, or managing non-life-threatening infections.

Stress triggers an enhancement of certain cognitive and sensory skills, making your senses sharper. It’s the reason even the tiniest noises in a horror movie can send shivers down your spine.

While these protective measures are beneficial in the short term, constantly shutting down essential long-term maintenance functions takes a toll on the body. If crucial functions like digestion and tissue repair are consistently sidelined, your body won’t get the repair it needs.

The consequence? Less surplus energy, leading to increased fatigue, a higher risk of ulcers, and greater vulnerability to infectious diseases.

Understanding how the body prioritizes during stress provides insight into the potential long-term effects. The upcoming lessons will delve into the impact of prolonged stress on our lives, shedding light on the consequences we may face in the extended journey of dealing with stress.

Next.

4️⃣ Stress can cause heart diseases (over time)

Ever noticed how a garden hose stiffens when water rushes through at high speed? Well, a similar phenomenon occurs within your body when stress kicks in – and it can have serious consequences over time.

Under stress, the muscles around the walls of your veins tighten, propelling blood through at a faster pace. As the blood reaches the heart, it forcefully collides with the heart walls, causing them to snap back like a rubber band and elevating your heart rate.

Additionally, arteries dilate to facilitate blood crossing into tissues, and smaller blood vessels work harder to regulate blood distribution.

This sets off a troublesome cycle: your body responds by building more muscles to control blood flow, causing smaller blood vessels to become stiffer.

This stiffness leads to increased blood pressure, prompting your body to produce more muscles to manage blood flow, and the cycle continues.

The rapid blood flow also triggers inflammation at the branch points of blood vessels, fostering the formation of blood clots – clusters of cells that obstruct blood flow. These branch points are widespread throughout your body, with no cell more than five cells away from a blood vessel.

When these blood clots break loose, they travel through your bloodstream, causing havoc by clogging smaller blood vessels and resulting in significant damage. If this occurs in a coronary artery, it can lead to a heart attack; in the brain, it can result in a stroke.

The toll stress takes on the cardiovascular system is substantial. Heart disease stands as the leading cause of death in the United States, underscoring the critical importance of understanding and managing stress to safeguard our heart health in the long run.

Onwards.

👉 Discover More:

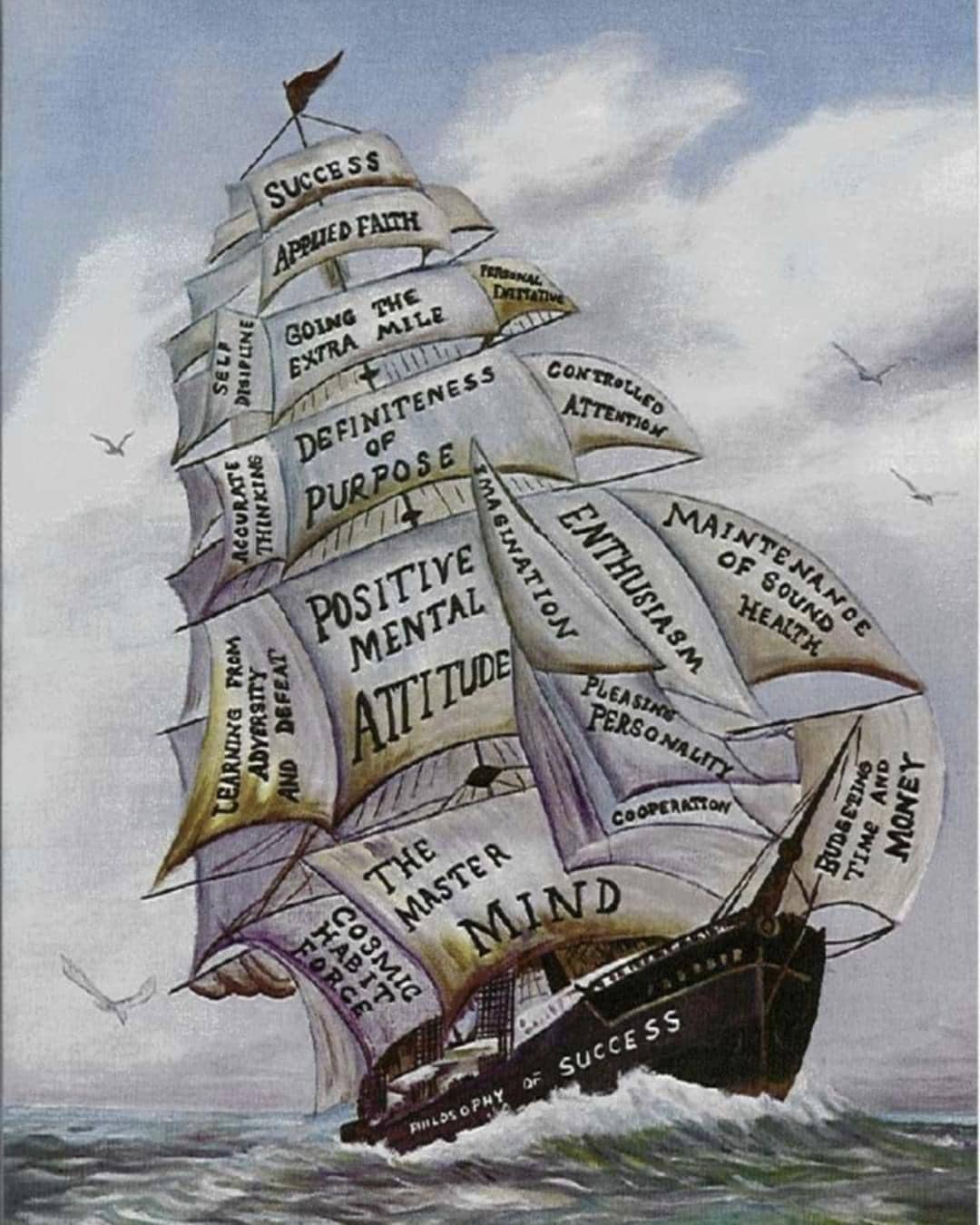

- 10 Powerful Lessons From “Think and Grow Rich”

- 12 Timeless Lessons From “The Daily Stoic”

- 12 Hidden Secrets From “The 48 Laws of Power”

5️⃣ Stress can increase the risk of diabetes (and other illnesses)

In our earlier discussion, we explored how the cardiovascular system plays a critical role in distributing energy to muscles during stress.

Now, let’s dig into where that energy comes from and how stress can heighten the risk of diabetes, leading to a cascade of health concerns.

Post-meal, your body boasts more nutrients than it currently needs. The surplus is broken down into amino acids, glucose, and fatty acids, stored in various locations like the liver and fat cells.

During stress, these nutrients are released into the bloodstream, providing muscles with the necessary energy to tackle the stressful situation.

However, if the situation doesn’t demand physical activity, the nutrients are reabsorbed into storage. Even this “false alarm” puts a strain on your body, as the process of releasing and reabsorbing nutrients consumes energy.

Constantly stressing over minor issues causes your body to waste energy on this repetitive nutrient shuffle, leading to increased fatigue.

This persistent stress can escalate into diabetes, presenting in two types. Type 1 diabetes emerges when the immune system destroys insulin-secreting cells in the pancreas, rendering the body unable to produce sufficient insulin.

Glucose reuptake is hindered, energy levels drop, organs malfunction, and insulin injections become necessary.

Type 2 diabetes occurs when cells resist insulin, often due to increased body fat. When fat cells reach their limit, insulin attempts to make them store more fat, but resistance develops.

Less glucose is taken up, elevating glucose levels in the bloodstream. The pancreas responds by producing more insulin, but the body resists it, resulting in pancreas cell destruction.

In both types, excess fat and glucose circulate in the bloodstream, contributing to atherosclerotic glomming – the thickening and hardening of artery walls. Chronic stress in individuals with diabetes exacerbates this condition, elevating the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other illnesses.

Understanding this connection between stress, energy transfer, and diabetes underscores the importance of managing stress for overall health and well-being.

Moving on.

6️⃣ Stress can increase depression

We all likely know someone who has experienced depression, a profound condition marked by an inability to feel pleasure, accompanied by overwhelming grief and guilt.

As studies project that depression will become the second-leading cause of global medical disability by 2020, understanding its effects on the body becomes crucial.

Interestingly, the changes in the brain and behavior of a depressed person closely mirror those experienced by someone under chronic stress.

For instance, stress depletes the neurotransmitter dopamine from pleasure pathways, diminishing the ability to experience pleasure. In a revealing study with rats, electrodes were implanted in the brain’s pleasure center.

The rats, when given access to a lever that stimulated the electrode, would pleasure themselves to the point of neglecting basic needs like food and sex.

However, when subjected to severe stress, the rats needed a higher intensity of electrical current to feel pleasure afterward. The intense stress made them less sensitive to enjoyable experiences.

Another shared aspect between stress and depression is their potential to lead to learned helplessness. In an experiment, rats quickly learned to avoid an electrified side of their cage after receiving a signal.

Yet, rats exposed to unpredictable shocks lost confidence in their problem-solving skills, ignoring even the predictable shocks. This phenomenon, known as learned helplessness, is common in depressed individuals who feel helpless to improve their situations.

These findings suggest that depression can be a stress-related condition, not necessarily induced by severe harm but rather by an inability to recover from distressing experiences.

Recognizing the parallels between stress and depression highlights the interconnected nature of mental and emotional well-being, urging us to prioritize strategies for effective stress management and recovery.

Next.

👉 Discover More:

- An Open Letter to My Future Son & Daughter: Step 2

- An Open Letter to My Future Son & Daughter: Step 1

- An Open Letter to My Future Son & Daughter: Intro

7️⃣ Stress affects our reproductive system (both for men and women)

In a world where “sex sells,” the reality is that sex itself can be a significant source of stress, influenced profoundly by the stress we experience. This stress has noteworthy effects on both men and women, intricately intertwining with our reproductive systems.

For men, stress manifests as premature ejaculation and difficulties achieving an erection. The process of getting an erection is regulated by the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system, responsible for calming the body.

Achieving an erection requires a state of calm and relaxation – the opposite of stress. Orgasms, however, occur when the sympathetic system increases heart and breathing rates.

To manage premature climaxing, sexual therapists recommend deep breaths, promoting parasympathetic activity.

Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation can, in turn, become major stressors themselves, creating a vicious cycle of performance anxiety for men.

In women, stress takes a toll on the hormone estrogen, leading to irregular menstrual cycles and a decline in libido. Estrogen is pivotal for women’s sexuality, increasing sensitivity in the genitals and other body parts.

Additionally, it influences brain regions active during sexual thoughts. Chronic stress disrupts the usual production of estrogen by impeding the conversion process from another hormone, androgen.

This disruption results in the accumulation of androgen, inhibiting various steps in the reproductive system.

As we’ve observed, long-term stress can exert significant strain on the body, impacting the delicate balance of our reproductive health.

In the upcoming discussions, we’ll explore ways to reduce and effectively cope with stress, promoting overall well-being and maintaining harmony in our reproductive systems.

Next.

8️⃣ Stress is unavoidable (so learn to manage it)

As we’ve explored the negative consequences of stress, it’s essential to recognize that these are just the surface of a much larger issue. Over time, scientific perspectives on how the body manages stress have evolved.

Initially, the belief was in the homeostatic principle, suggesting that problems in the body could be corrected with localized adjustments, akin to ordering smaller toilet tanks during a water shortage in a city like San Francisco.

However, the reality is more complex. The body operates under the principle of allostasis, where interconnected systems necessitate many small adjustments in various locations.

In the San Francisco analogy, not only would you reduce toilet tank sizes, but you’d also encourage water conservation and alter food import strategies. Allostatic adjustments during stress responses are intricate, impacting numerous body functions.

Balancing allostatic systems at low stress hormone levels is comparable to balancing two children on a seesaw – relatively manageable. However, when high stress floods the body with hormones, it becomes akin to balancing two elephants.

It’s not impossible, but it requires a significant amount of energy that could be more productively used for long-term building projects within the body, like cell repair and antibody production.

Adjusting the elephants delicately on the seesaw may still result in some damage in the garden, given the elephants’ size and clumsiness. Similarly, fixing one major problem in the body often disrupts other balances.

This intricate interplay explains why stress has widespread effects on various aspects of life, influencing sleep, memory, eating, growth, immunity, pregnancy, aging, addiction, and more.

Understanding and navigating this complex web of interactions is key to finding ways to manage and mitigate the impact of stress on our overall well-being.

Onwards.

9️⃣ Take responsibility for your stress (it helps to minimize it)

Feeling stressed? The strategies you choose, whether tackling problems directly or seeking support from friends, both prove effective in stress reduction.

Taking responsibility for stressful situations can empower you, restoring a sense of control over your life. In nursing homes, studies revealed that giving elderly individuals responsibility for daily decision-making positively impacted their lives.

This included increased activity, happiness, and health, with a remarkable 50% reduction in mortality observed over the study period.

When the elderly were encouraged to solve tasks, their health indices improved, while assistance from staff had the opposite effect. The key was residents actively taking responsibility for their tasks, demonstrating the stress-reducing benefits.

Recognizing the aspects of stress you can solve versus those where perception needs adjustment is crucial. For instance, if you’re stressed about an upcoming test, proactive studying before the exam can alleviate stress.

However, if the test doesn’t go well, reframing the meaning of a poor grade—focusing on the learning experience rather than the grade—becomes a valuable coping strategy.

Moreover, both giving and receiving social support emerge as highly effective stress prevention measures. Having someone to lean on provides substantial stress relief, but offering support is equally stress-reducing.

Studies show that, on average, married individuals tend to be healthier than singles, benefiting from the reciprocal emotional support within couples.

Professionals in roles where they provide valuable social services, like judges and court practitioners, experience better mental and physical health in old age.

This emphasizes the profound impact of social support, both in giving and receiving, on overall well-being and stress resilience.

Onwards.

🔟 Your income affects your stress levels (so maximize it)

While we’ve discussed various stressors, some, like poverty, extend beyond isolated incidents and contribute to chronic stress. The impact of your place in society, particularly socioeconomic status, plays a substantial role in stress levels, influencing resistance to illness and mortality rates.

Being in poverty is associated with both physical and mental stressors. Jobs with high physical demands and low job security, common in lower-income roles, leave individuals with little control over their work situations, leading to elevated stress levels.

Additionally, the financial constraints of poverty limit opportunities for stress relief through vacations or hobbies.

This connection between poverty and stress-related diseases persists even after individuals escape poverty, as demonstrated in a study of elderly nuns. The conditions they grew up in influenced disease patterns in old age, despite living in the same conditions for 50 years.

Interestingly, you don’t have to be poor to experience stress-related effects similar to those in poverty. The subjective feeling of being poor, measured by your perceived socioeconomic status in comparison to your peers, can have comparable consequences.

Studies in affluent countries reveal that beyond reaching a certain standard of living ensuring well-being, the amount of money in your bank account becomes less critical to stress levels than how you perceive your financial well-being relative to others.

Understanding the societal impact on stress levels underscores the need for holistic approaches to well-being that address not only individual stressors but also broader social and economic factors influencing health outcomes.

Moving on.

1️⃣1️⃣ Income inequality promotes lack of trust (and hence more stress for all)

Understanding how socioeconomic factors influence health goes beyond individual circumstances; it encompasses broader community dynamics. In this context, income inequality and social capital play pivotal roles in shaping the health of societies.

Communities with high social capital, characterized by strong social networks and resources available in times of need, experience greater equity and better health outcomes.

This social capital is akin to financial resources, offering support in various forms, such as neighbors assisting with childcare during work overtime.

In these communities, people are less socially isolated, leading to better diffusion of health information and reduced psychological stress as individuals feel safer.

Social capital can be measured through indicators like voter turnout, reflecting a sense of community involvement and the belief that individuals can effect change at both local and national levels.

Conversely, income inequality has a detrimental impact on community health. Higher levels of income inequality correlate with increased mortality rates across all ages and races at local and regional levels.

Despite the wealth of a nation, if income inequality is significant, the overall health of its community members tends to decline. For instance, the United States, while economically affluent, experiences higher mortality rates compared to Canada, which is less wealthy but more egalitarian.

The benefits of greater equality extend to both the rich and the poor. Societies with better income equality see improved health for both groups.

Reduced stress among the wealthy is attributed to a sense of security and lower inclination to isolate themselves, while the poor experience better health outcomes as they are not left behind.

In essence, poverty and stress are societal issues that extend beyond financial struggles, reflecting a society’s tolerance for leaving segments of the population behind.

This tolerance can lead to increased hostility, distrust, and crime, resulting in physical and psychological stressors affecting both the rich and the poor. Recognizing the interconnectedness of these factors is essential for creating healthier and more equitable communities.

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers Review ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️✩

Stress, originally designed to keep us alive in life-or-death situations, has become a pervasive issue in the modern world, affecting our health negatively.

From everyday challenges to imagined scenarios, stressors are abundant, impacting both the rich and the poor. To safeguard our well-being, it’s crucial to learn effective coping mechanisms and address societal factors contributing to stress.

Discover and engage in a personalized stress-relieving activity regularly. While many endorse physical exercise, it’s essential to find an activity that resonates with you, as there’s no one-size-fits-all solution.

The key is to identify an activity that effectively pulls you out of a stressful state of mind. Commit time to this chosen activity daily to promote better stress management and overall well-being.

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers Quotes

| Robert M. Sapolsky Quotes |

|---|

| “If I had to define a major depression in a single sentence, I would describe it as a ‘genetic/neurochemical disorder requiring a strong environmental trigger whose characteristic manifestation is an inability to appreciate sunsets.” |

| “On an incredibly simplistic level, you can think of depression as occurring when your cortex thinks an abstract thought and manages to convince the rest of the brain that this is as real as a physical stressor.” |

| “Most people who do a lot of exercise, particularly in the form of competitive athletics, have unneurotic, extraverted, optimistic personalities to begin with. (Marathon runners are exceptions to this.)” |

| “Genes are rarely about inevitability, especially when it comes to humans, the brain, or behavior. They’re about vulnerability, propensities, tendencies.” |

| “Freud was fascinated with depression and focused on the issue that we began with—why is it that most of us can have occasional terrible experiences, feel depressed, and then recover, while a few of us collapse into major depression (melancholia)? In his classic essay ‘Mourning and Melancholia’ (1917), Freud began with what the two have in common. In both cases, he felt, there is the loss of a love object.” |

| “Depression is not generalized pessimism, but pessimism specific to the effects of one’s own skilled action.” |

| “…when doing science (or perhaps when doing anything at all in a society as judgmental as our own), be very careful and very certain before pronouncing something to be a norm – because at that instant, you have made it supremely difficult to ever again look objectively at an exception to that supposed norm.” |

| “Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine on a large scale.” |

| “Everything in physiology follows the rule that too much can be as bad as too little. There are optimal points of allostatic balance.” |

| “A large percentage of what we think of when we talk about stress-related diseases are disorders of excessive stress-responses.” |

| “This is the critical point of this book: if you are that zebra running for your life, or that lion sprinting for your meal, your body’s physiological response mechanisms are superbly adapted for dealing with such short-term physical emergencies.” |

| “In a world of stressful lack of control, an amazing source of control we all have is the ability to make the world a better place, one act at a time.” |

| “It takes surprisingly little in terms of uncontrollable unpleasantness to make humans give up and become helpless in a generalized way.” |

| “Subjected to enough uncontrollable stress, we learn to be helpless—we lack the motivation to try to live because we assume the worst; we lack the cognitive clarity to perceive when things are actually going fine, and we feel an aching lack of pleasure in everything.” |

| “Memory can be dramatically disrupted if you force something that’s implicit into explicit channels.” |

| “Fear is the vigilance and the need to escape from something real. Anxiety is about dread and foreboding and your imagination running away with you. Much as with depression, anxiety is rooted in a cognitive distortion. In this case, people prone toward anxiety overestimate risks and the likelihood of a bad outcome.” |

| “Prior to the monotheistic Yahweh, the gods made sense, in that they had familiar, if supra-human appetites—they didn’t just want a lamb shank, they wanted the best lamb shank, wanted to seduce all the wood nymphs, and so on. But the early Jews invented a god with none of those desires, who was so utterly unfathomable, unknowable, as to be pants-wettingly terrifying. So even if His actions are mysterious, when He intervenes you at least get the stress-reducing advantages of attribution—it may not be clear what the deity is up to, but you at least know who is responsible for the locust swarm or the winning lottery ticket. There is Purpose lurking, as an antidote to the existential void.” |

| “Whenever you inhale, you turn on the sympathetic nervous system slightly, minutely speeding up your heart. And when you exhale, the parasympathetic half turns on, activating your vagus nerve in order to slow things down (this is why many forms of meditation are built around extended exhalations).” |

More from thoughts.money

- The Science of Success: 17 Proven Steps to Achieve Any Goal

- 8 Proven Money Lessons From “The FALCON Method”

- A Must-Know Lesson From “The First Rule of Mastery”

- 5 Early Retirement Tips From “Playing with FIRE”

- 7 Life Lessons From “Die with Zero”

- 4 Money Lessons From “Tax-Free Wealth”

- 5 Practical Tips From “The Value of Debt in Building Wealth”

- 8 Emotional Intelligence Lessons From “The Power of Nunchi”

- 6 Down-to-Earth Lessons From “How I Invest My Money”

- 8 Life Lessons From “The Geometry of Wealth”

- 8 Money Lessons From “The Laws of Wealth”

- 11 Stress-Free Lessons From “Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers”

- 8 Health Tips From “The Stress Code”

- 8 Psychology Lessons From “The Behavioral Investor”

- 7 Life Secrets From “The Happiness Equation”

- 11 Humankind Lessons From “Sapiens”

- 7 Health Lessons From “The Upside of Stress”

- 9 Smart Lessons From “Emotional Intelligence”

- 10 Controversial Truths From “The Hour Between Dog and Wolf”

- 10 Powerful Sales Lessons From “The 3-Minute Rule”

- 7 Strategies for Wealth and Happiness by Jim Rohn

- 9 Lessons to Apply Today From “The Daily Laws”

- 7 Must-Know Truths From “What I Learned Losing a Million Dollars”

- 4 Never-Before-Published Lessons From “Pathways to Peace of Mind”

- 4 Long-Lost Lessons From “Outwitting the Devil”

- 8 Untold Secrets From “Napoleon Hill’s Golden Rules”

- 12 Hidden Secrets From “The 48 Laws of Power”

- 8 Practical Lessons From “The New Trading for a Living”

- Financial Wisdom From “Charlie Munger”

- Power Lessons From “13 Things Mentally Strong People Don’t Do”

- 4 Investing Lessons From “Trade Like a Stock Market Wizard”

- 7 Investing Lessons From “How to Make Money in Stocks”

- 12 Timeless Lessons From “The Daily Stoic”

- 6 Simple Lessons From “The Little Book of Common Sense Investing”

- 7 Super Ideas From “One Small Step Can Change Your Life”

- 8 Killer Lessons From “The Millionaire Real Estate Agent”

- 7 Counter-Intuitive Life Lessons From “Lives of the Stoics”

- 5 Important Life Lessons From “Million Dollar Habits”

- 6 School Lessons From “Why A Students Work for C Students”

- 9 Financial Freedom Lessons From “Rich Dad’s Cashflow Quadrant”

- 6 Wealth Lessons From “Millionaire Success Habits”

- 7 Unspoken Truths From Rich Dad’s “Retire Young Retire Rich”

- 9 Must-Know Lessons From “The Intelligent Investor”

- 14 Life Lessons From “The Snowball”

- 5 Investing Lessons From “Warren Buffett’s Ground Rules”

- 8 Money Secrets From “The Richest Man in Babylon”

- 10 Powerful Lessons From “Think and Grow Rich”

- These Are the Top 9 Lessons From “Rich Dad, Poor Dad”

- These Are the Top 5 Lessons From “How Highly Effective People Speak”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “Burn the Boats”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “The Power of Now”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “The Psychology of Selling”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “Mind Over Money”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons From “The War Of Art”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “The Dip”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “Ikigai”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “The 10X Rule”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck”

- These Are the Top 3 Lessons from the “Man’s Search For Meaning”

- Should You Start a Dropshipping Business? (If Yes, How?)

- Should You Buy an REO (Real-Estate Owned) Property?

- This Is What Pet Insurance Covers

- This Is How Much Cash You Should Keep in the Bank

- This Is How to Make a Living Will (In 5 Simple Steps)

- These Are the Top 7 Dividend ETFs

- These Are the Top 10 ETFs (U.S. & International)

- These Are the Top 7 Money Market Accounts

- These Are the Top 9 Budget-Friendly Cities for Christmas

- This Is How FDIC, NCUA, and SIPC Protect Your Money

- Should You Use an Oven or Air Fryer?

- Should You Use a Dishwasher or Hand Wash?

- This Is the Difference Between a Salary and Hourly Pay

- This Is the Definition of a Christmas Club Account

- This Is How to Open an IRA (In 5 Simple Steps)

- If You Rent, It’s OK (Here Are 10 Reasons Why)

- Is There a Best Time to Buy or Sell Stocks? (Let’s See)

- This Is What the Value Line Composite Index Tells Investors

- This Is the Difference Between Technical and Fundamental Analysis

- This Is What Alpha and Beta Means in Investing

- This Is What Banking Desert Means

- So, You Want to Invest in Stocks (Here Are 5 Simple Steps)

- Do You Really Need Life Insurance? (Probably Yes)

- These Are the 6 Worst Student Loan Mistakes You Can Make

- Should You Apply for a Private or a Federal College Loan?

- Here’s the Difference Between Fixed and Adjustable Rate Mortgages

- This Is How Much the American Dream Costs Now

- This Is How to Become a Millionaire in 6 Simple Steps

- This Is What Famous Billionaires Did As Their First Job

- Here Are the 9 Most Common Motorcycle Types

- This Is the Difference Between Hard and Soft Money

- This Is How to Exercise Your Stock Warrants

- After Thanksgiving Comes Cyber Monday (What’s the Story?)

- So Long Mr. Munger: A Life Well Spent

- So, You Wanna Buy a Busa? (Here’s All You Need to Know)

- Capitalism Makes the World Go Round? (Let’s Find Out)

- Interested in Bitcoin Mining? (Here’s How It Works)

- The World’s Largest Companies (By Revenue)

- The World’s Most Profitable Companies (By Net Income)

- This Is How Much Jay-Z Is Worth

🔥 Daily Inspiration 🔥

Trying to get without first giving is as fruitless as trying to reap without having sown.

The Bible states that we reap what we sow. The most fertile soil in the world is barren unless seeds have been properly planted, cultivated, and nurtured.

The relationship between giving and getting is constant in everything you do.

To succeed in any endeavor, you must first invest a generous portion of your time and talents if you expect ever to earn a return on your investment.

You have to give before you get. It’s all a matter of attitude. You may occasionally be disappointed if you are not rewarded for your efforts.

Still, if you demand payment for your services before you render them, you can expect a lifetime of disappointment and frustration.

You can anticipate a bountiful harvest of life’s most significant rewards if you cheerfully do your best before asking for compensation.

— Napoleon Hill